Personas have a long history in digital products and services. In fact, you’ve probably built a few yourself. They come in varying levels of fidelity and traditionally document key demographic information about your average or likely users. Personas can be incredibly helpful for teams, especially newly established ones, to help build context and guardrails around who they are building for. The problem with personas is they haven’t really changed much in the last few decades. If you run a basic search right now it will generate a hundred of the same templates with a standard array of demographic inputs; fake persona name (i.e. John, Jennifer, Barbara), age, job, city/state, marital status, and a generic stock photo. The issue with this information is that when combined, they often perpetuate harmful stereotypes. If personas were a cake, the bias would come pre-mixed. It takes effort to reimagine the next generation of personas and deliberately avoid the common pitfalls of our past templates.

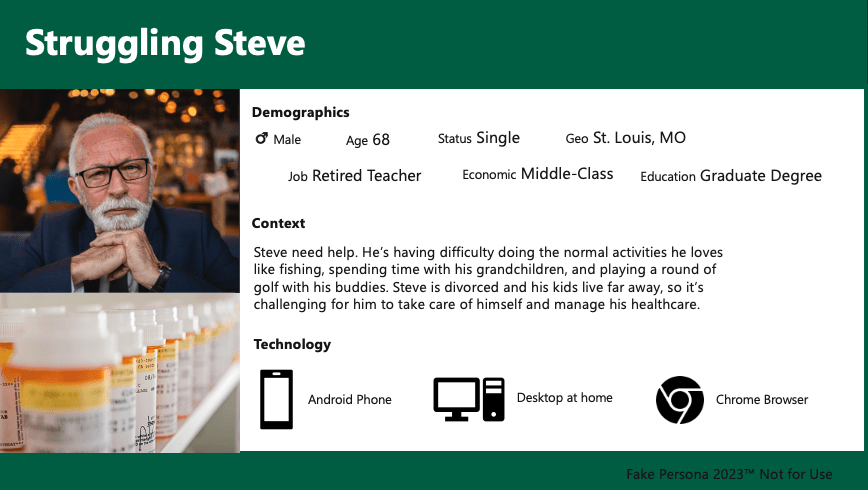

Take this persona for instance, the “Struggling Steve” is an amalgam of what I see in traditional personas most frequently. It pictures a cisgender male in his 60s, with a myriad of demographic attributes, perhaps a small section for context, needs/challenges, and his relationship with technology (which usually boils down to which browser he prefers). In this scenario, Steve is experiencing pain for no other obvious reason than he is aging. He has little social support, can’t afford healthcare, and is seen pictured with a cornucopia of medications making it seem as though he’s managing multiple conditions. While some of this may be true and there might actually be a Steve out there with these exact issues (if so, sorry Steve), it’s unlikely that this information is driven by real, reliable, novel data. Instead, this persona bolsters the stigma surrounding elders by framing them as poor, unhealthy, digitally inept, and alone. This is not at all representative of the incredibly diverse and brilliant older adults I’ve spoken to as a UX Researcher. In this case, we’ve allowed our common bias and social conditioning to inspire a harmful prediction about the people we’re creating for and in turn, it impacts all the marginalized people around us. This is especially true for personas that feature people of color alongside demographic information such as a low socio-economic status, lack of social support, or similar attributes that perpetuate false stereotypes about these communities. Personas such as these frequently rely on assumptions about users/customers from the top down. The ultimate misconception I hear many leaders make is that they “know their users,” but they have done little to no research to validate or explore their assumptions. And you’ve heard that old saying about assumptions, right?

If the purpose of your persona is to elevate the voices of your diverse users and build empathy for them, don’t just throw a photo of a person of color on the top and neglect the rest of their personal story.

Common questions to ask yourselves when building UX personas

- Who are our actual users (not who we think they are)?

- Are we building personas or archetypes? Or maybe both?

- Does this persona help you know which features to prioritize or who to test your product with?

- Does it tell you how your users approach new technology, their digital literacy, or their comfort level with new features?

Building the next generation of personas

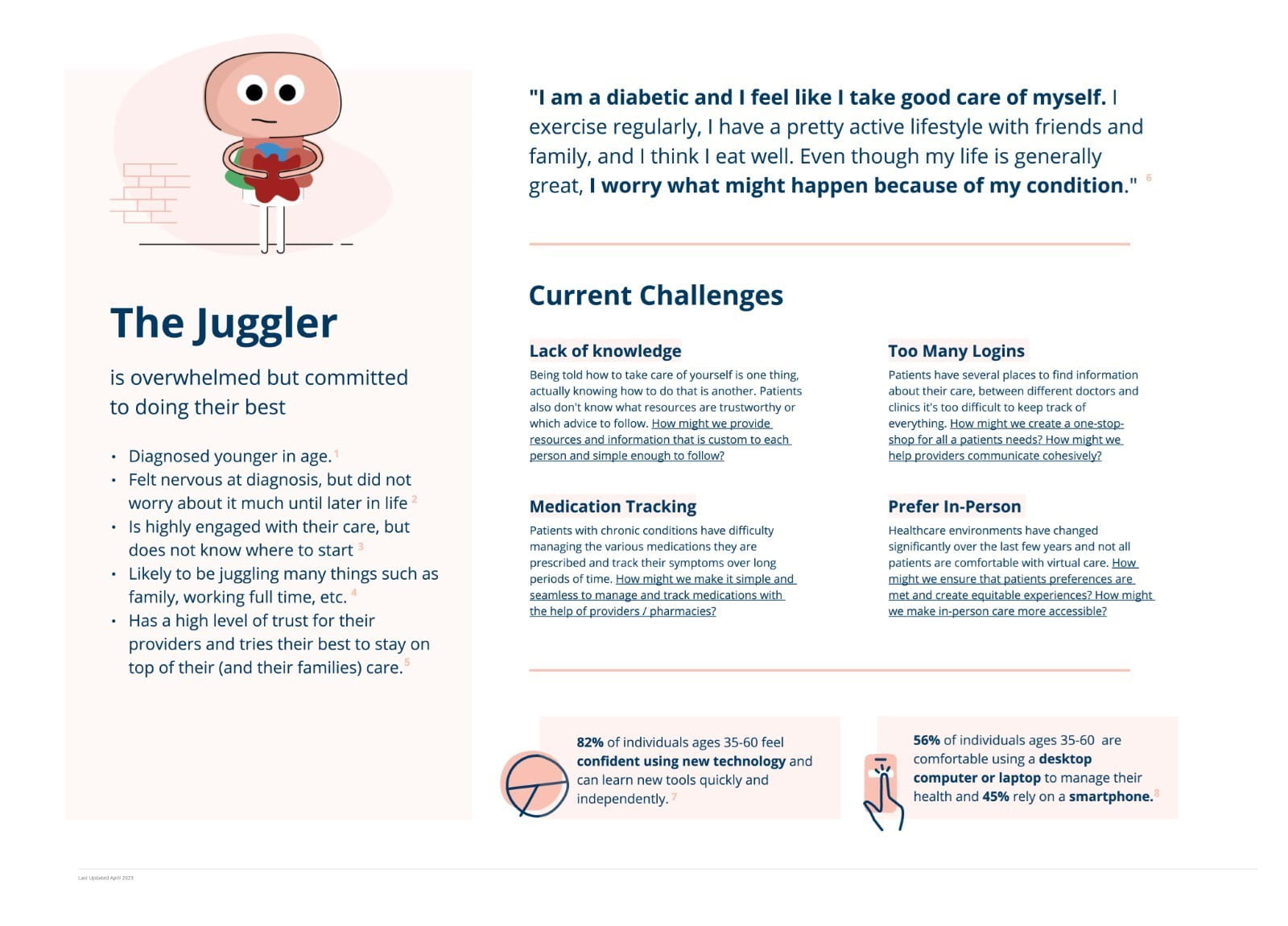

Recently, a client asked us to build personas for their healthcare customers with type 2 diabetes. They were tired of seeing the same unhelpful market research personas and wanted something truly built for product teams who need to understand how customers use technology and navigate digital experiences. They needed a persona that would help push forward design decisions. Because we were building for marginalized users who often have the highest touchpoints in healthcare, it was especially important to deconstruct any preconceived assumptions and call-in areas of bias.

We started the process with collaborative brainstorming and assumption mapping. This was a cross-functional workshop between the internal team and the client stakeholders, to document all the knowledge, data, and beliefs about users. We also collected and analyzed all the existing research on users, including the market research personas and customer archetypes that had already been built. Based on these insights we lead the team through a deep empathy activity (centered around Spoon Theory) to help put ourselves in the shoes of someone managing type 2 diabetes. Then we conducted the most important activity, research with actual users. We spoke with a dozen customers who are managing type 2 diabetes (along with other chronic conditions) and tested some of our thinking. We also asked open-ended questions and let participants walk us through a day in their lives. This allowed us to ground our research in the lived experiences of our users and formulate insights bottom-up (users to leaders). Through these activities we realized that users often flow in and out of personas depending on where they are at in their care journey and what they are experiencing in their day-day lives. In doing so, we crafted a spectrum using two personas that represented the most common experiences amongst our participants. This is a version of one of the personas we ended up with (scrubbed of client information of course).

Original design by Brooke Bratrud, project lead by Caylie O’Neil

To ensure that no “Steve’s” ended up being the face of our clients’ users we had a designer create custom characters that represented emotions rather than race, age, or occupation. We included data from our research about when participants were diagnosed (as opposed to how old they are now), their comfort with using new technology, and a quote about their experience. We focused on their current challenges and asked, ‘how might we?’ questions to encourage further exploration and ideation. To say these personas went over well is an understatement, they were an overwhelming success and have prompted more work, having us explore other chronic conditions.

So, the next time you set out to build a persona maybe use this as a template. Ask yourselves tough questions out the gate. And pressure test your personas against common stereotypes. Consider the impact your personas might have on your colleagues who themselves may be marginalized and those who might experience undue harm from being subjected to them. Focus on the things that make meaning for your users, on their actual lived experiences, and you might even try asking them what they think.

This story was originally published at WestMonroe.com. West Monroe is a digital services firm born in tech and built for business.

Join Over 7,500 Fielding Alumni Located Around The World!

Change the world. Start with yours.™

Get Social